A perhaps somewhat topical question given the events that continue to play out around us, it is one that in this post I am going to suggest we should be asking ourselves. Before you groan at the thought of yet another blog post on the pandemic, rest assured that I am not going to mention the ‘C’ word.

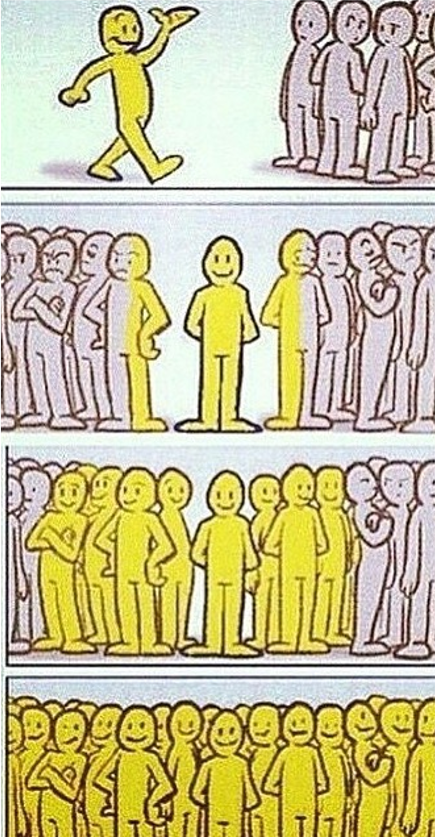

A budding area of research in the last couple of decades has examined the role of emotions in leadership. A particular topic that researchers have considered is the phenomenon of emotional contagion – the idea that our moods can be transferred to those around us.

Various scholars (e.g. Sigal Barsade) have found that through mimicry of facial expressions, body language and tone of voice, our mood can be picked up by others around us. Further, the mirror neuron (of which we have a fair few in our brain) is designed to do exactly what it says on the tin – mirror others and their emotions.

We all have a little yellow person in our lives - that one who perks up any room they come into

Why does this matter?

It matters because the effects of positive emotion are hugely beneficial and the effects of negative emotion can be hugely damaging. We know that positive emotions can broaden our thinking and awareness, with research reporting that super useful things to organisations – like creativity, curiosity, performance and good team dynamics – are all enhanced when we are in a more positive frame of mind (see Shawn Achor’s TED talk on the Happiness Advantage – one of my all time favourites).

Negative emotions, on the other hand, tend to close down our thinking – usually taking us to the basics of fight or flight reactions – in response to the thing that has triggered our negativity. Translated into the workplace, this means a deficit of all of those things just mentioned – less creativity, curiosity… and all the rest. And in the context of leading a team, this can have serious implications for effectiveness.

What should you do?

Firstly, try to be more emotionally self-aware; understanding your emotions and recognising what you’re feeling means you know when you need to take steps to limiting their negative impact. Then, pay attention to how you express them. Most importantly, think about your body language - since most of the messages we transmit about how we’re feeling are non-verbal. Then take steps to change that in a situation where you know you need your team to be on point. In other words: fake it.

Final thoughts

I know I promised not to mention the pandemic, however perhaps you will allow me to make just one small reference to it as I close. If you find yourself struggling with your emotion in a given moment – one strategy could be to draw on the Hands, Face, Space government guidance that I am sure will remain forever etched in our minds.

Hands – wash your hands of the emotion you are feeling – you are in control of your emotions, not the other way around.

Face – the way we outwardly convey emotion is perceived by those around us. So if you want to make sure you don’t spread negative emotion – fake it ‘til you make it with your face and your tone.

Space – if you know you struggle with faking it – remove yourself from the situation. Give your team space rather than potentially spreading your negativity on them.

Happy spreading!